Why are we so bad at getting what we want?

Seemingly, nobody has what they want. Every child wants a life that is not their own. Every adult, seemingly, wants a raise, or a new boss, or a new job altogether. We want a bigger yard, a larger fence, or the neighbor’s house. The divorce rate alone suggests something about people wanting what they don’t have, to say nothing of infidelity rates (though I don’t pretend that it’s not all very complicated— I’m sure it is!). Everywhere we look, it might appear that we don’t have what we want. Or else, we’re all wanting something.

First and foremost, of course we want things! There are clear evolutionary advantages to wanting—it's a driving force behind innovation and progress. We might even argue that desire itself has a certain nobility. What else would propel us to launch a man into space or create a microprocessor? Still, subtler theories may explain our relentless wanting. The Hedonic Treadmill, for instance, suggests that we habituate to the things we get, leaving us perpetually unsatisfied. Rene Girard’s Mimetic Theory, which posits that all desire is borrowed from others, also offers valuable insights.

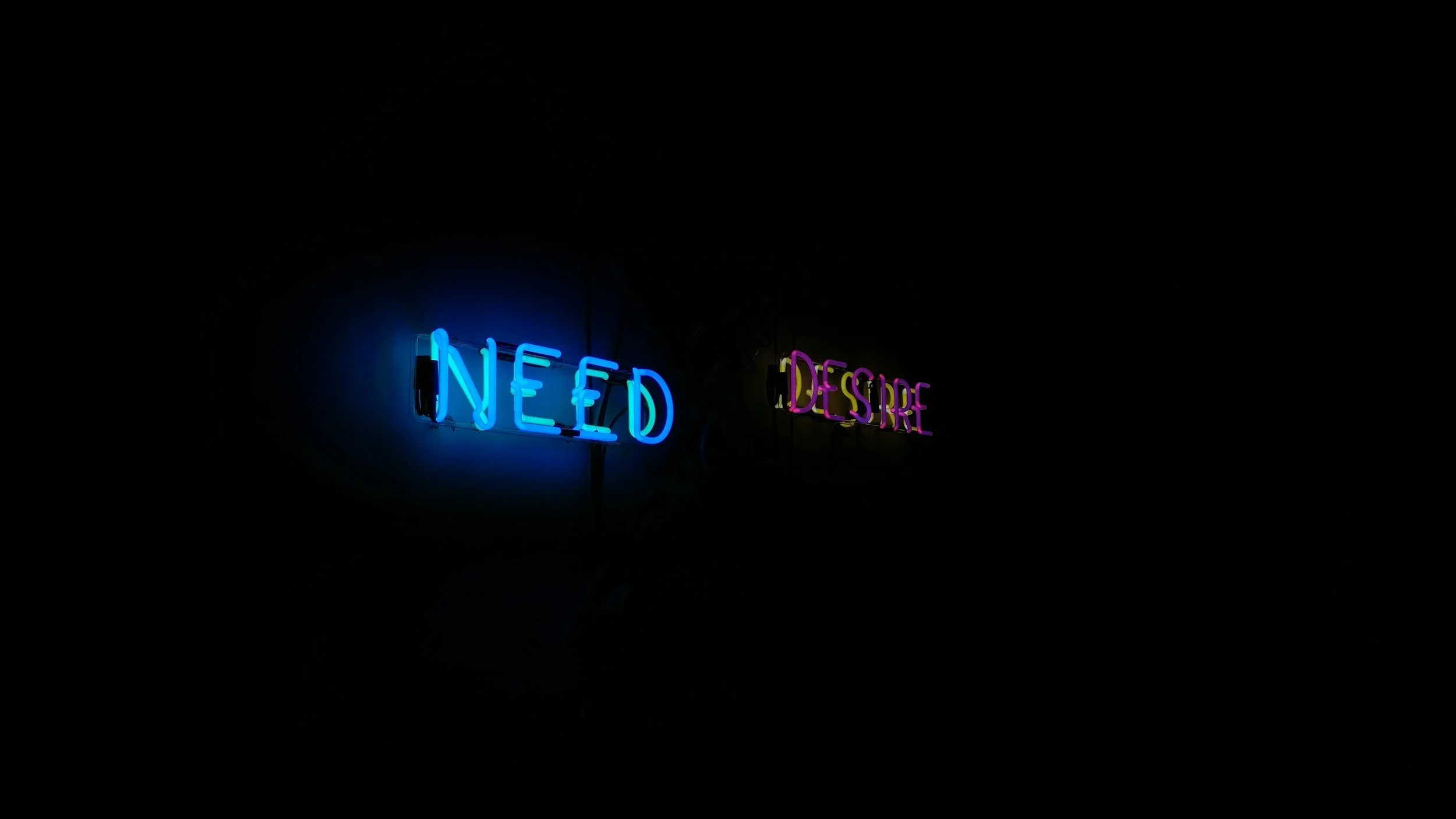

Still, those theories concern themselves (mainly) with why we want things in the first place, not why we seem so often to not be able to get what we want. These theories don’t explain why it’s so hard to stay on a diet, even when we say we want to lose weight or be healthier, or why it’s so difficult to stop a bad habit even after we commit ourselves to never ever ever doing it again. This feels like a different issue. Namely, why is it so hard to get what we want?

“It’s like my brain is at war with itself,” said one senior in high school summer school a week after graduation after being asked why he didn’t do the last three homework assignments despite having ample motivation to do so; he in fact needed to pass this course in order to receive a diploma and begin practicing with his prospective college sports team. While we may be amazed by this student and their situation, some sober part of us has to acknowledge the truth of his statement. Maybe “war” is a bit dramatic, but there’s a conflict, or a tension— in all of our minds. If this weren’t true we would never have the need to apologize. Our actions would align perfectly with our intention and we would never have the need to apologize or to feel regret for acting wrongly. This of course is not the case and many of us frequently find occasion to apologize for acting in contradiction to our intentions. But even if we could somehow manage to never need to apologize, that is to avoid undesirable behavior, still so many of us aren’t actually doing, or getting, or achieving what we want. Our careers may not be what we had hoped, nor our friendships, or our relationships— or any number of important facets of our lives— our tennis game, even. Which, again, begs the question: why are we so bad at getting what we want?

If you feel an instinct to protest this premise, I invite you to consider all the things you want but do not yet have. Why not? What are the chances you’ll achieve all of them? And what are the chances you won’t? Perhaps you’re willing to part ways with some of your desires, but the idea of not achieving certain key desires may rightly haunt you. And still, it’s possible you won’t get what you want. Why is that? And what will decide what we do get? What is it about our minds that makes it so easy to want but so difficult to execute on that desire and actually achieve it?

This book is predicated on the idea that the reason we are so bad at getting what we want is due to a lack of control—specifically, control over our own minds. Neuroscientists may call it cognitive control, cognitive scientists may refer to it as self-regulation, and educators interested in helping students achieve self-control might term it executive function. For the purposes of this book, I will treat all of these terms more or less synonymously. The issue is control—specifically, self-control. This book is aimed at helping people become more executive and gain more control over themselves and their lives.