On Executive Functions: The Barriers and Strategies Protocol

Like the brain itself, the topic of executive functions is complicated and nobody can seem to agree on what it actually is or what it consists of. Much of Laurie Faith’s work, actually, is predicated on this problem. The introductions of her books tend to go this way: nobody can agree on what executive function is, how many of them there are, and whether or not there are 3 executive functions, or 11 or even 33 (which we’ll get to!). Furthermore, knowing that there are 3 and not 11 may not be as helpful as getting students to think about better solving their own problems. Compare this to the way research on ADHD went. We studied it, we came up with names and meds, we told everybody what it was and then we told kids they had it. Still (seemingly) it’s below chance that a student who has been told he has ADHD has been told anything of compensatory strategies or how they can function effectively in school or at work with it. Instead, admitting that our collective understanding of the executive functions is not where it should or could be, Faith’s model starts in on the problem solving, the goal being: help kids to gain more control of themselves in order to solve the problems of their lives. It’s a powerful approach and this book owes a tremendous debt to its ideas. The model goes like this:

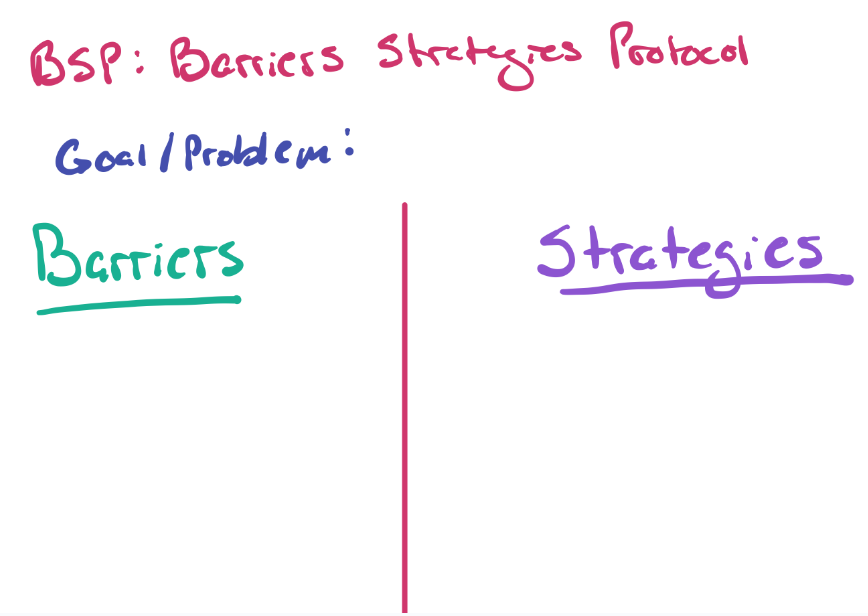

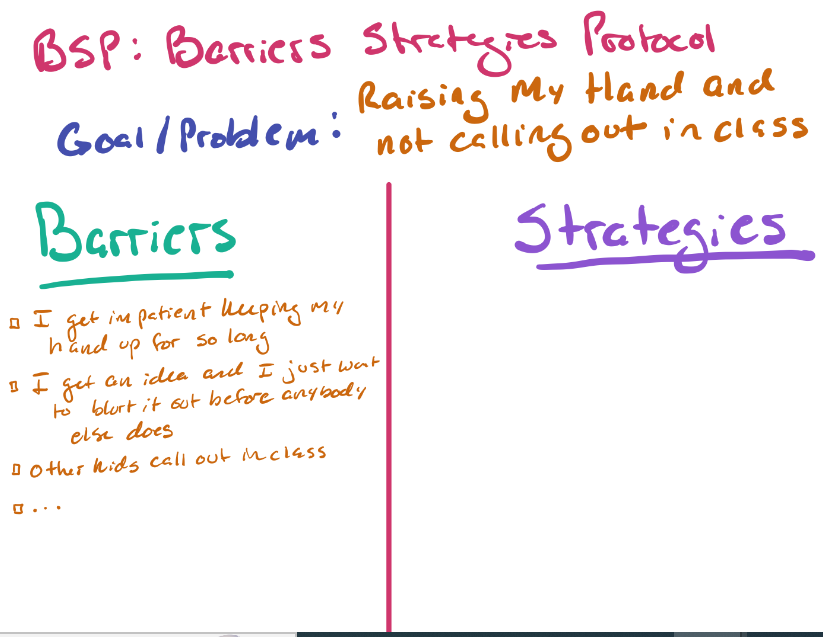

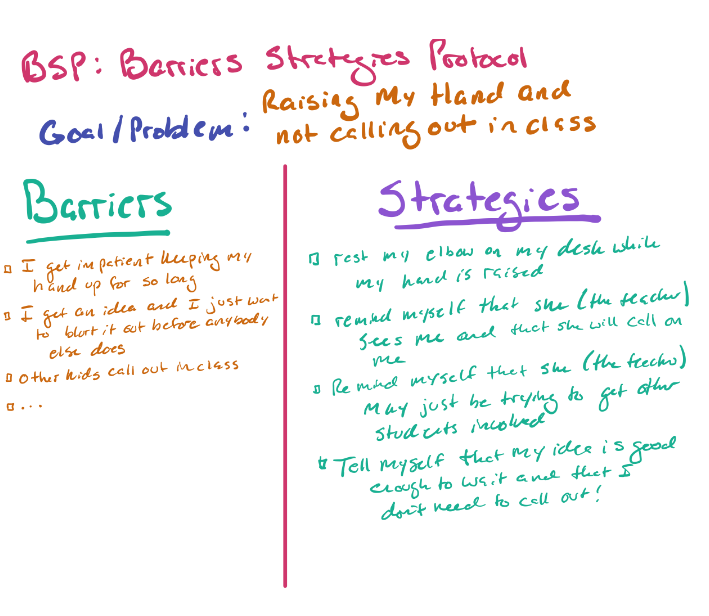

Identify a problem or a goal. List out all of the barriers that keep you from achieving that goal. Then, list out strategies to help you overcome that barrier to accomplish that goal. This can be done in a group setting, say with a group of students who are struggling to not call out during class, or it can be facilitated during a one-on-one conversation with a student who is trying to get into their dream college, or hold onto a scholarship, or get an internship.

One of the important features of the exercise is the emphasis on co-authorship. The student or child should be listing their self-identified barriers and their self-identified strategies. This will necessarily slow down the process. This is a feature, not a bug. This will also necessarily be… well, bad. Certainly at first. And maybe for a while. Again, this is much of the point. You are there to facilitate the process, not solve any of it for them.

Too often we’re solving problems for kids. We arrange their rides to and from practice, we pack their lunch, we take them shopping for school supplies and while we do we are carrying around the list, we tell them what to do and what not to do and maybe occasionally we’ll take the time to tell them why— and then we wonder why they’re not good at solving problems! They haven’t had the reps. This exercise is designed to put the ball back in the kids’ court, and to let them struggle (safely and in a supportive environment) to work towards solving their problems. And the beautiful thing is: they get better at it over time!

Again, it’s worth emphasizing that you do play a crucial role in this exercise. The child is not simply completing this on their own. You are the much-needed facilitator. Your primary tool: questions. Prompt them to think deeper and to focus on what they can control. And guide them to use the protocol to think more systematically about their problems.

Let’s look at an example together. First, a student (or group of students) is struggling to raise their hand and not call out. Through a series of questions like, “what are some barriers that might make it difficult for us to raise our hand?” Get the student to consider all that stands in the way of their goal. Feel free to explore these responses and to refine them a bit as you record them with the student. Eventually, you will produce a short list of everything that student thinks impedes them from their goal. Often times, I will be amazed by the levels of introspection on display here. Especially in relation to more complex goals like getting good grades or improving their GPA, students will identify their cell phones as barriers to their own success, their habits during their free periods, their lack of routine upon arriving home from school, their peers at their lunch table, and even their attitude while completing the homework. This is fertile ground! When students give you answers like these, the sky’s the limit. It’s clear that they’re thinking hard about their own problems and that they’re willing to think about themselves as contributing to these problems in some non-zero way. If you see any signs of this, encourage it!

Crucially, again, these are their ideas— however crude or incomplete. Use this to your advantage. These are not your ideas that you’ve hoisted onto them. They’ve identified these things as barriers to their own goals. Use this not only to better understand the student’s situation but to help the student come up with tailor-made solutions.

Once a student has done their best to list out as many barriers as they can think of, the next step is to have them attempt to generate strategies they can use to overcome the barriers they just identified.

There will absolutely be a need to facilitate these conversations, but the point is to have the student generate and then assess their own solutions to their problems. You may feel tempted throughout the process to laugh or pass judgment on the quality of their suggested strategies or to suggest that one may not actually be effective in practice. Simply ask them about their strategies, why they think they could work, and if they imagine there being any way in which they don’t work. This is ultimately the point of the exercise: to help students get better at solving their own problems. This requires us, the adults or facilitator, to give them the latitude and the opportunity to genuinely attempt to solve it on their own, with a little guidance.

While I do think there are a ton of merits to this approach… it’s simple, there’s a versatility to it and it can be used in a number of situations (not to mention it’s great for a number of ages), it is difficult to track over time. In Faith’s book she makes a number of recommendations for using anchor charts or putting these charts on the board and reminding the class of the strategies they’d generated and this could be really useful, at a certain age. I’ve found, too, that while the Barriers and Strategies Protocol is recommended as a whole class activity, when it comes to older students (high school), it’s much more impactful as a one-on-one exercise. This too poses a problem of how to track and maintain this chart over time. My own team, in an academic support capacity, has experimented with using google docs for individual students to create a running document of BSPs and follow up notes (something I’ll touch on more later).

It’s worth noting that this is simply one approach to executive functions and to facilitating self-control in educational environments. This approach in particular attempts to be more practical, and actionable. But there is much to be gleaned from the more theoretical approaches to executive functions, as we’ll see.